What Do Centrioles Do In An Animal Cell

| Prison cell biological science | |

|---|---|

| centrosome | |

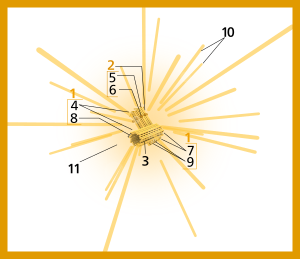

Components of a typical centrosome:

|

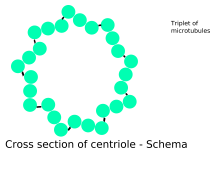

Cross-section of a centriole showing its microtubule triplets.

In cell biological science a centriole is a cylindrical organelle composed mainly of a poly peptide chosen tubulin.[ane] Centrioles are found in most eukaryotic cells, but are not nowadays in conifers (Pinophyta), flowering plants (angiosperms) and well-nigh fungi, and are just present in the male gametes of charophytes, bryophytes, seedless vascular plants, cycads, and Ginkgo.[2] [three] A bound pair of centrioles, surrounded by a highly ordered mass of dense material, called the pericentriolar material (PCM),[4] makes upwardly a structure chosen a centrosome.[1]

Centrioles are typically fabricated up of 9 sets of short microtubule triplets, arranged in a cylinder. Deviations from this construction include crabs and Drosophila melanogaster embryos, with ix doublets, and Caenorhabditis elegans sperm cells and early embryos, with ix singlets.[5] [vi] Boosted proteins include centrin, cenexin and tektin.[7]

The main function of centrioles is to produce cilia during interphase and the aster and the spindle during cell division.

History [edit]

The centrosome was discovered jointly by Walther Flemming in 1875 [8] [ix] and Edouard Van Beneden in 1876.[10] [9]Edouard Van Beneden fabricated the starting time observation of centrosomes equally composed of 2 orthogonal centrioles in 1883.[11] Theodor Boveri introduced the term "centrosome" in 1888[12] [9] [13] [xiv] and the term "centriole" in 1895.[15] [ix] The basal body was named by Theodor Wilhelm Engelmann in 1880.[16] [9] The pattern of centriole duplication was beginning worked out independently by Étienne de Harven and Joseph G. Gall c. 1950.[17] [eighteen]

Role in prison cell division [edit]

Centrioles are involved in the arrangement of the mitotic spindle and in the completion of cytokinesis.[19] Centrioles were previously idea to be required for the germination of a mitotic spindle in animal cells. However, more than recent experiments have demonstrated that cells whose centrioles have been removed via laser ablation can still progress through the Thou1 stage of interphase earlier centrioles tin can be synthesized subsequently in a de novo manner.[20] Additionally, mutant flies lacking centrioles develop normally, although the adult flies' cells lack flagella and cilia and as a upshot, they die soon after nascence.[21] The centrioles tin can cocky replicate during cell division.

Cellular organization [edit]

Centrioles are a very important part of centrosomes, which are involved in organizing microtubules in the cytoplasm.[22] [23] The position of the centriole determines the position of the nucleus and plays a crucial office in the spatial arrangement of the cell.

3D rendering of centrioles

Fertility [edit]

Sperm centrioles are important for 2 functions:[24] (i) to grade the sperm flagellum and sperm movement and (2) for the evolution of the embryo after fertilization. The sperm supplies the centriole that creates the centrosome and microtubule system of the zygote.[25]

Ciliogenesis [edit]

In flagellates and ciliates, the position of the flagellum or cilium is determined by the mother centriole, which becomes the basal body. An inability of cells to use centrioles to make functional flagella and cilia has been linked to a number of genetic and developmental diseases. In item, the inability of centrioles to properly migrate prior to ciliary assembly has recently been linked to Meckel–Gruber syndrome.[26]

Fauna evolution [edit]

Electron micrograph of a centriole from a mouse embryo.

Proper orientation of cilia via centriole positioning toward the posterior of embryonic node cells is critical for establishing left-correct asymmetry, during mammalian development.[27]

Centriole duplication [edit]

Before Dna replication, cells comprise two centrioles, an older mother centriole, and a younger girl centriole. During jail cell sectionalization, a new centriole grows at the proximal end of both female parent and daughter centrioles. After duplication, the two centriole pairs (the freshly assembled centriole is at present a girl centriole in each pair) will remain attached to each other orthogonally until mitosis. At that point the female parent and daughter centrioles separate dependently on an enzyme chosen separase.[28]

The two centrioles in the centrosome are tied to 1 another. The mother centriole has radiating appendages at the distal end of its long axis and is attached to its daughter at the proximal stop. Each daughter cell formed after prison cell division will inherit one of these pairs. Centrioles start duplicating when Deoxyribonucleic acid replicates.[xix]

Origin [edit]

The last common ancestor of all eukaryotes was a ciliated cell with centrioles. Some lineages of eukaryotes, such equally land plants, do non accept centrioles except in their motile male person gametes. Centrioles are completely absent from all cells of conifers and flowering plants, which do not have ciliate or flagellate gametes.[29] Information technology is unclear if the last mutual ancestor had one[30] or two cilia.[31] Important genes such as centrins required for centriole growth, are only found in eukaryotes, and not in bacteria or archaea.[30]

Etymology and pronunciation [edit]

The word centriole () uses combining forms of centri- and -ole, yielding "piddling central part", which describes a centriole's typical location near the eye of the cell.

Singular centrioles [edit]

Typical centrioles are fabricated of nine triplets of microtubules organized with radial symmetry.[32] Centrioles tin vary the number of microtubules and can be made of nine doublets of microtubules (every bit in Drosophila melanogaster) or 9 singlets of microtubules equally in C. elegans. Atypical centrioles are centrioles that do not have microtubules, such every bit the Proximal Centriole-Like found in D. melanogaster sperm,[33] or that have microtubules with no radial symmetry, such every bit in the distal centriole of human spermatozoon.[34] Singular centrioles may have evolved at to the lowest degree eight times independently during vertebrate development and may evolve in the sperm later internal fertilization evolves.[35]

It wasn't clear why centriole go atypical until recently. The atypical distal centriole forms a dynamic basal circuitous (DBC) that, together with other structures in the sperm cervix, facilitates a cascade of internal sliding, coupling tail beating with head kinking. The atypical distal centriole's properties suggest that it evolved into a transmission system that couples the sperm tail motors to the whole sperm, thereby enhancing sperm function.[36]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Eddé, B; Rossier, J; Le Caer, JP; Desbruyères, E; Gros, F; Denoulet, P (1990). "Posttranslational glutamylation of alpha-tubulin". Science. 247 (4938): 83–five. Bibcode:1990Sci...247...83E. doi:10.1126/science.1967194. PMID 1967194.

- ^ Quarmby, LM; Parker, JD (2005). "Cilia and the cell cycle?". The Journal of Jail cell Biology. 169 (v): 707–10. doi:10.1083/jcb.200503053. PMC2171619. PMID 15928206.

- ^ Silflow, CD; Lefebvre, PA (2001). "Assembly and movement of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Institute Physiology. 127 (iv): 1500–1507. doi:ten.1104/pp.010807. PMC1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Lawo, Steffen; Hasegan, Monica; Gupta, Gagan D.; Pelletier, Laurence (Nov 2012). "Subdiffraction imaging of centrosomes reveals higher-order organizational features of pericentriolar fabric". Nature Cell Biology. 14 (11): 1148–1158. doi:10.1038/ncb2591. ISSN 1476-4679. PMID 23086237. S2CID 11286303.

- ^ Delattre, G; Gönczy, P (2004). "The arithmetics of centrosome biogenesis" (PDF). Journal of Cell Science. 117 (Pt 9): 1619–30. doi:10.1242/jcs.01128. PMID 15075224. S2CID 7046196.

- ^ Leidel, S.; Delattre, G.; Cerutti, 50.; Baumer, 1000.; Gönczy, P (2005). "SAS-half-dozen defines a protein family unit required for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and in human cells". Nature Cell Biological science. 7 (2): 115–25. doi:10.1038/ncb1220. PMID 15665853. S2CID 4634352.

- ^ Rieder, C. L.; Faruki, S.; Khodjakov, A. (Oct 2001). "The centrosome in vertebrates: more than a microtubule-organizing centre". Trends in Cell Biology. xi (10): 413–419. doi:x.1016/S0962-8924(01)02085-ii. ISSN 0962-8924. PMID 11567874.

- ^ Flemming, W. (1875). Studien uber die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Najaden. Sitzungsgeber. Akad. Wiss. Wien 71, 81–147

- ^ a b c d e Bloodgood RA. From central to rudimentary to primary: the history of an underappreciated organelle whose fourth dimension has come. The primary cilium. Methods Cell Biol. 2009;94:3-52. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)94001-2. Epub 2009 December 23. PMID 20362083.

- ^ Van Beneden, E. (1876). Contribution a l'histoire de la vesiculaire germinative et du premier noyau embryonnaire. Bull. Acad. R. Belg (2me serial) 42, 35–97.

- ^ Wunderlich, V. (2002). "JMM - By and Present". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 80 (9): 545–548. doi:10.1007/s00109-002-0374-y. PMID 12226736.

- ^ Boveri, T. (1888). Zellen-Studien Two. Die Befruchtung und Teilung des Eies von Ascaris megalocephala. Jena. Z. Naturwiss. 22, 685–882.

- ^ Boveri, T. Ueber das Verhalten der Centrosomen bei der Befruchtung des Seeigel-Eies nebst allgemeinen Bemerkungen über Centrosomen und Verwandtes. Verh. d. Phys.-Med. Ges. zu Würzburg, Northward. F., Bd. XXIX, 1895. link.

- ^ Boveri, T. (1901). Zellen-Studien: Uber die Natur der Centrosomen. Iv. Fischer, Jena. link.

- ^ Boveri, T. (1895). Ueber die Befruchtungs und Entwickelungsfahigkeit kernloser Seeigeleier und uber die Moglichkeit ihrer Bastardierung. Arch. Entwicklungsmech. Org. (Wilhelm Roux) two, 394–443.

- ^ Engelmann, T. W. (1880). Zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Flimmerzellen. Pflugers Arch. 23, 505–535.

- ^ Wolfe, Stephen L. (1977). Biology: the foundations (First ed.). Wadsworth. ISBN9780534004903.

- ^ Vorobjev, I. A.; Nadezhdina, E. S. (1987). The Centrosome and Its Office in the System of Microtubules. International Review of Cytology. Vol. 106. pp. 227–293. doi:x.1016/S0074-7696(08)61714-three. ISBN978-0-12-364506-7. PMID 3294718. . See too de Harven's ain recollections of this work: de Harven, Etienne (1994). "Early on observations of centrioles and mitotic spindle fibers by transmission electron microscopy". Biology of the Cell. 80 (2–iii): 107–109. doi:10.1111/j.1768-322X.1994.tb00916.ten. PMID 8087058. S2CID 84594630.

- ^ a b Salisbury, JL; Suino, KM; Busby, R; Springett, M (2002). "Centrin-2 is required for centriole duplication in mammalian cells". Current Biology. 12 (15): 1287–92. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01019-9. PMID 12176356. S2CID 1415623.

- ^ La Terra, South; English, CN; Hergert, P; McEwen, BF; Sluder, 1000; Khodjakov, A (2005). "The de novo centriole associates pathway in HeLa cells: cell cycle progression and centriole assembly/maturation". The Periodical of Cell Biology. 168 (v): 713–22. doi:10.1083/jcb.200411126. PMC2171814. PMID 15738265.

- ^ Basto, R; Lau, J; Vinogradova, T; Gardiol, A; Forest, CG; Khodjakov, A; Raff, JW (2006). "Flies without centrioles". Cell. 125 (vii): 1375–86. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. PMID 16814722. S2CID 2080684.

- ^ Feldman, JL; Geimer, S; Marshall, WF (2007). "The mother centriole plays an instructive role in defining cell geometry". PLOS Biology. v (half-dozen): e149. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050149. PMC1872036. PMID 17518519.

- ^ Beisson, J; Wright, M (2003). "Basal body/centriole assembly and continuity". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 15 (one): 96–104. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00017-0. PMID 12517710.

- ^ Avidor-Reiss, T., Khire, A., Fishman, E. Fifty., & Jo, K. H. (2015). Atypical centrioles during sexual reproduction. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 3, 21. Chicago

- ^ Hewitson, Laura & Schatten, Gerald P. (2003). "The biological science of fertilization in humans". In Patrizio, Pasquale; et al. (eds.). A color atlas for human being assisted reproduction: laboratory and clinical insights. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. iii. ISBN978-0-7817-3769-2 . Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Cui, Cheng; Chatterjee, Bishwanath; Francis, Deanne; Yu, Qing; SanAgustin, Jovenal T.; Francis, Richard; Tansey, Terry; Henry, Charisse; Wang, Baolin; Lemley, Bethan; Pazour, Gregory J.; Lo, Cecilia W. (2011). "Disruption of Mks1 localization to the mother centriole causes cilia defects and developmental malformations in Meckel-Gruber syndrome". Dis. Models Mech. 4 (ane): 43–56. doi:10.1242/dmm.006262. PMC3008963. PMID 21045211.

- ^ Babu, Deepak; Roy, Sudipto (1 May 2013). "Left–right disproportion: cilia stir up new surprises in the node". Open Biology. 3 (5): 130052. doi:ten.1098/rsob.130052. ISSN 2046-2441. PMC3866868. PMID 23720541.

- ^ Tsou, MF; Stearns, T (2006). "Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle". Nature. 442 (7105): 947–51. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..947T. doi:10.1038/nature04985. PMID 16862117. S2CID 4413248.

- ^ Marshall, W.F. (2009). "Centriole Evolution". Current Stance in Jail cell Biological science. 21 (1): fourteen–19. doi:x.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.008. PMC2835302. PMID 19196504.

- ^ a b Bornens, M.; Azimzadeh, J. (2007). "Origin and Evolution of the Centrosome". Eukaryotic Membranes and Cytoskeleton. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 607. pp. 119–129. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74021-8_10. ISBN978-0-387-74020-1. PMID 17977464.

- ^ Rogozin, I. B.; Basu, Yard. K.; Csürös, Thou.; Koonin, East. Five. (2009). "Analysis of Rare Genomic Changes Does Not Support the Unikont-Bikont Phylogeny and Suggests Cyanobacterial Symbiosis equally the Bespeak of Principal Radiation of Eukaryotes". Genome Biological science and Evolution. 1: 99–113. doi:x.1093/gbe/evp011. PMC2817406. PMID 20333181.

- ^ Avidor-Reiss, Tomer; Gopalakrishnan, Jayachandran (2013). "Edifice a centriole". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 25 (i): 72–7. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.ten.016. PMC3578074. PMID 23199753.

- ^ Blachon, S; Cai, 10; Roberts, G. A; Yang, K; Polyanovsky, A; Church, A; Avidor-Reiss, T (2009). "A Proximal Centriole-Like Construction is Nowadays in Drosophila Spermatids and Tin Serve as a Model to Report Centriole Duplication". Genetics. 182 (one): 133–44. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.101709. PMC2674812. PMID 19293139.

- ^ Fishman, Emily L; Jo, Kyoung; Nguyen, Quynh P. H; Kong, Dong; Royfman, Rachel; Cekic, Anthony R; Khanal, Sushil; Miller, Ann L; Simerly, Calvin; Schatten, Gerald; Loncarek, Jadranka; Mennella, Vito; Avidor-Reiss, Tomer (2018). "A novel atypical sperm centriole is functional during human fertilization". Nature Communications. nine (1): 2210. Bibcode:2018NatCo...nine.2210F. doi:ten.1038/s41467-018-04678-8. PMC5992222. PMID 29880810.

- ^ Turner, M., N. Solanki, H.O. Salouha, and T. Avidor-Reiss. 2022. Atypical Centriolar Composition Correlates with Internal Fertilization in Fish. Cells. 11:758, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/xi/5/758

- ^ Khanal, Southward., Grand.R. Leung, A. Royfman, Due east.50. Fishman, B. Saltzman, H. Bloomfield-Gadelha, T. Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, and T. Avidor-Reiss. 2021. A dynamic basal circuitous modulates mammalian sperm motion. Nat Commun. 12:3808.. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24011-0

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centriole

Posted by: maserneash1938.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Do Centrioles Do In An Animal Cell"

Post a Comment